What is Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy?

Pelvic floor physical therapy (PFPT) is also known as pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). PFPT is considered to be a first-time, conservative treatment for pelvic floor disorders. Patients are given various exercises in order to improve “pelvic floor muscle strength, endurance, power, relaxation, or a combination of these”.

This approach includes strengthening and stretching of trunk, leg and pelvic muscles, relaxation and coordination exercises, education for patients in order to self-manage their condition and prevent recurrence, using equipment such as biofeedback, and the use of other modalities such as heat, ice, or electrical stimulation.

What is the Pelvic Floor?

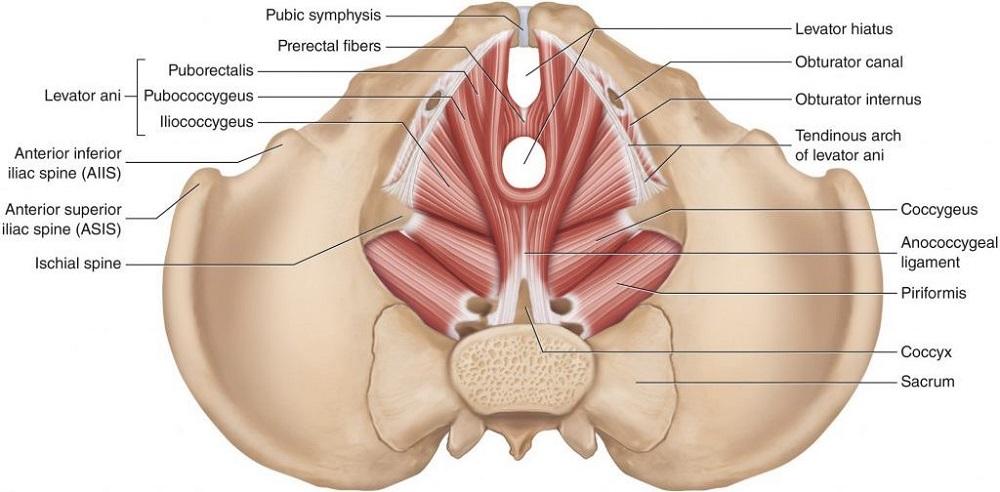

The pelvic floor is a dome-shaped, muscular sheet that separates the pelvic cavity above from the perineal area below. This cavity encompasses the bladder, intestines, and the uterus in females. The primary role of the pelvic floor muscles is to support the abdominal and pelvic viscera, to maintain the continence of urine and feces, and to allow for voiding, defecation, sexual activity, and childbirth. Deep pelvic floor muscles include the coccygeus muscles & the levator ani muscle complex (puborectalis, pubococcygeus, & iliococcygeus muscles).

What are Pelvic Floor Disorders?

● Low-Tone Pelvic Floor Disorders1 (not enough tension on the pelvic floor muscles)

○ Stress urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, pelvic organ prolapse, anal incontinence, peripartum and postpartum

● High-Tone Pelvic Floor Disorders1 (too much tension on the pelvic floor muscles)

○ Pelvic floor myofascial pain, dyspareunia and vaginismus, vulvodynia

Which Exercises Can Be Done?

A 2010 review by Marque, Stothers, and Macnab discusses the problems with prescribing the proper amount, frequency, and duration of exercise needed in order to improve pelvic floor muscle function. The authors state that in general, the American College of Sports Medicine and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention have given public health recommendations that are comprehensive and evidence-based for regular exercise. These recommendations vary based on health maintenance, increasing muscular strength or endurance, and maximizing strength, as well as individual factors. The dosage for general exercise is fairly well-studied, but how does this compare to pelvic floor muscle training? The issues remain similar between regular skeletal muscle and the pelvic floor muscles, and the goals are also similar – improving overall health and training the muscles for strength and endurance. However, the anatomy of the pelvic floor muscles is drastically different from regular skeletal muscle. The pelvic floor is made up of a group of muscles and connective tissue that are composed of two layers. The superficial perineal muscles and the deep pelvic diaphragm extend across the base of the pelvis.

These two layers act as a sling to support and protect the pelvic organs, bladder, and parts of the spine. They are also composed of more type I fibers, which are slow-twitch fibers that are necessary for prolonged contraction. Additionally, they do require type II fibers (fast-twitch fibers) in order to quickly contract. The pathophysiology of the pelvic floor muscles is multifaceted and there are many reasons why someone may be experiencing pelvic floor dysfunction. Pelvic floor dysfunction may be a consequence of human evolution, childbirth, lifestyle, and aging. Additionally, constipation, living a sedentary lifestyle, menopause and advanced aging may also contribute to dysfunction, such as stress urinary incontinence. When there is a pelvic floor dysfunction, the muscle fiber length and contractile force are both affected. For example, muscles that are distensile and stiff cannot generate as much force. Since pelvic muscles have a role in supporting the pelvic floor and its contents, they have a higher percentage of slow-twitch fibers in order to maintain tone and contraction, with the exception being during voiding and defecation. Overall, it is important to train both fast and slow twitch fibers – fast twitch fibers for the initial contraction, and slow twitch in order to improve endurance and maintain that contraction.

Table 2 shows the evolution of pelvic floor muscle training and how it has changed over time, especially since Kegel discovered the benefits of pelvic floor awareness and strengthening of the pelvic floor. Unfortunately, there is still no consensus on the optimal regimen to maintain pelvic floor function or remediate dysfunction.

For pelvic floor muscle training, a muscle training protocol that is using a combination of the training principles of overload, specificity, and reversibility are encouraged to be followed. Overload means that overtime, the target muscle will need to work harder than last time in order to make improvements. Specificity means that the target muscle being trained should be performing physical activity that is closely related to its functional tasks – Kegel exercises meet this specificity requirement. Reversibility means that the benefits of the exercises performed are reversible if the patient does not incorporate the exercises into their daily routine. Therefore, adherence to a prescribed exercise regimen is critical to see improvements in pelvic floor dysfunction.

Currently, there are no set recommendations, however, increased levels of physical activity overall are associated with improvements in pelvic floor muscle function. This study stated that increased activity can benefit overall body strength and fitness, which would have a positive effect on stress urinary incontinence.

Further research is needed.

Kegels – A 3 Step Process

Kegel exercises are also known as pelvic floor exercises, and these are named after Dr. Arnold Kegel who developed this form of exercise which helps to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles. He originally developed these exercises in 1948 in order to prevent the need for surgery, as Dr. Kegel believed surgery was inefficient and unnecessary at times.

Kegels are exercises that include an isometric contraction of the pelvic floor muscles. The typical way to describe the activation of pelvic floor muscles during a Kegel exercise is to “stop urinating mid-flow.” These exercises are helpful for producing sufficient strength, coordination, and endurance that are all necessary in order to appropriately and actively recruit the pelvic floor muscles. The following are 3 steps to an effective Kegel, or pelvic floor muscle contraction:

1.) Learn how to tighten the muscles around the vaginal/anal area.

2.) Contract the vaginal and rectal muscles – when this is done properly, you should feel the muscles around the anus tighten slightly.

3.) Practice Kegel exercises in a quiet environment with no distractions and see how long you can hold the contraction and how many you are able to perform before fatiguing. Do not perform more than 5-10 reps at a time, and perform each contraction with a 3-5 second hold.

Electromyographic Biofeedback Use in Pelvic Floor Muscle Training

One barrier for clinicians is the lack of access to proper equipment that is needed in order to provide patients with adequate pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT). Common pieces of equipment used in order to increase effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training are typically electromyographic biofeedback, weighted vaginal cones, and electrical stimulation1. A 2020 randomized controlled trial examined the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training with and without electromyographic biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women.

The purpose of this study was to examine the effectiveness of PFMT plus electromyographic biofeedback (group 1), or PFMT alone (group 2) for stress and mixed urinary incontinence in women. Six hundred female participants aged 18 or older who were presenting with stress or mixed urinary incontinence between February 2013 and July 2016 were included in the study. Three-hundred were randomized into PFMT plus electromyographic biofeedback and 300 were placed into the PFMT alone group. Both groups were given 6 appointments with continence therapists over a 16 week period. The participants in the biofeedback PFMT group were given supervised PFMT and a home exercise program, which also included the incorporation of electromyographic biofeedback during the clinic appointments and at home. The group without the biofeedback received supervised PFMT in the clinic and a home exercise program. The primary outcome measure was a self-reported severity of urinary incontinence, which was the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-urinary incontinence short form (ICIQ-UI SF), and this was given at 24 months.

In terms of results, the mean ICIQ-UI SF scores at 24 months were 8.2 in the biofeedback PFMT group and 8.5 in the PFMT group, which were not significantly different from one another. In conclusion, there was no evidence at 24 months that showed an important difference in severity of urinary incontinence between PFMT plus electromagnetic biofeedback and PFMT alone1. Therefore, the use of electromyographic biofeedback with PFMT should not be recommended, as it was not found to be superior.

Why Does This Matter?

A 2018 systematic review by Radzimińska et al. had the goal of identifying the impact of pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) on the quality of life (QoL)of women with urinary incontinence (UI). This was based on 2,394 women in 24 studies that were selected to be in the review. In these studies, they found that at the end of treatment, patients who were a part of the experimental group with PFMT had statistically significant improvements in QoL. The authors stated that based on this literature review, it is demonstrated that PFMT is an effective treatment for UI in women, and PFMT significantly improves QoL in women with UI, “which is an important determinant of their physical, mental, and social functioning.”5

References

1.) Hagen S, Elders A, Stratton S, et al. Effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training with and without electromyographic biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2020:m3719. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3719

2.) Kegel’s Exercise : Females. Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Kegel%27s_Exercise_:_Females. Accessed July 26, 2021.

3.) Marques A, Stothers L, Macnab A. The status of pelvic floor muscle training for women. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4(6):419-424. doi:10.5489/cuaj.10026

4.) Pelvic Floor Anatomy. Physiopedia. https://www.physio-pedia.com/Pelvic_Floor_Anatomy. Accessed July 26, 2021.

5.) Radzimińska A, Strączyńska A, Weber-Rajek M, Styczyńska H, Strojek K, Piekorz Z. The impact of pelvic floor muscle training on the quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: a systematic literature review. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2018;Volume 13:957-965. doi:10.2147/cia.s160057

6.) Wallace SL, Miller LD, Mishra K. Pelvic floor physical therapy in the treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction in women. Current Opinion in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2019;31(6):485-493. doi:10.1097/gco.0000000000000584

7.) What is Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy? What is Pelvic Floor Physical Therapy? | Good Shepherd Penn Partners. https://www.pennpartners.org/blog/what-is-pelvic-floor-physical-therapy. Accessed July 26, 2021.